Disclaimer: this review was made possible thanks to a screener provided by the film’s UK distributor, The Movie Partnership.

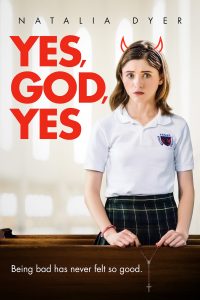

Karen Maine’s feature directorial debut, coming-of-age Catholic teen girl dramedy Yes, God, Yes, aims to fit itself squarely at the intersection of two recent acclaimed entries in the general coming-of-age dramedy space: Greta Gerwig’s 2017 revelation Lady Bird and Desiree Akhavan’s complex 2018 adaptation of The Miseducation of Cameron Post. Neither comparison does Maine’s film any real favours. In fairness, they also wouldn’t do any real favours to films that are better than the ‘resolutely fine’ that Yes, God, Yes is, but they still don’t help Maine’s case all that much. Especially the Cameron Post comparisons, since both are about prejudiced religious dogma attempting to shame and stifle the growth and desires of teenagers, and teenaged girls specifically in our protagonists, around the turn of the millennium.

Karen Maine’s feature directorial debut, coming-of-age Catholic teen girl dramedy Yes, God, Yes, aims to fit itself squarely at the intersection of two recent acclaimed entries in the general coming-of-age dramedy space: Greta Gerwig’s 2017 revelation Lady Bird and Desiree Akhavan’s complex 2018 adaptation of The Miseducation of Cameron Post. Neither comparison does Maine’s film any real favours. In fairness, they also wouldn’t do any real favours to films that are better than the ‘resolutely fine’ that Yes, God, Yes is, but they still don’t help Maine’s case all that much. Especially the Cameron Post comparisons, since both are about prejudiced religious dogma attempting to shame and stifle the growth and desires of teenagers, and teenaged girls specifically in our protagonists, around the turn of the millennium.

Whilst Cameron Post focussed on conversion therapy camps, Yes, God, Yes centres on abstinence and judgemental repression. Our protagonist, Alice (Stranger Things’ Natalia Dyer), a 16-year-old Catholic schoolgirl who is intensely awkward and somewhat adrift from the spirit of her faith but religiously committed to its ideals regardless. One night, however, an innocent AOL chat word game sees her receiving an unsolicited dick and vag pic from a rando that brings long simmering repressed sexual desires in her bubbling up to the surface. At exactly the wrong time, too, as her badly-handled shame and inner conflict over the idea of masturbation has arrived just when she’s become the victim of a salacious rumour spread around the school about a non-existent tryst between her and another boy which paints her as a slut, her genuine protestations of not knowing what “salad tossing” even is going unbelieved. With even the school’s father (Timothy Simons) passive-aggressively judging her for this imagined transgression, Alice signs up for the a four-day isolated retreat, Kirkos, in the hopes that its vague promises of “change” and “help” will successfully suppress these temptatious urges burning up inside of her.

Now, admittedly, I am not religious and, despite initial years spent around my Nan (who used to be very religious) and a forced daily Christian prayer during my time in Junior School (which has always struck me as weird since the school wasn’t officially religious), have had no experiences with these sorts of abstinence courses or repressive religious retreats. So, there is every chance that I just don’t understand or can’t relate to whatever specifics there are in Maine’s screenplay – she’s been open about the film’s semi-autobiographical nature in interviews. And there are the seeds of a strong viewpoint in both her screenplay and direction. There’s a palpable sense of isolating frustration and shame rattling through Alice’s every action, a mixture of that religious damnation and arbitrary social pariah of high school politicking melding together with the hormonal rush of a sexual awakening to leave her adrift lacking any real help to navigate these new emotions. That’s reinforced by Todd Antonio Somodevilla’s cinematography which keeps centring Alice in frame in often powerless or accusatory blocking, highlighting her inability to communicate to even her one alleged friend (Francesca Reale coincidentally also from Stranger Things) yet still being corralled and manipulated into confession of trauma for no real end purpose.

Frustratingly, however, I found Maine’s execution of these various themes and emotions to be rather like the methods of the Kirkos retreat: deliberately vague without a clear end goal, based around repeated gestures lacking deeper meaning, and hoping that a grand summarising speech at the end of it all can make up for that often directionless nature. It’s a film which evidently has many ideas, but Maine doesn’t embrace the contradictions, emotional turmoil or complexity the material requires, like Akhavan did for Cameron Post, and I didn’t feel like there was all that much specificity or detail on display. Any character who isn’t Alice frankly doesn’t convince as a character, they just aren’t developed enough to function as anything deeper than that scene’s sounding board or passive-aggressive antagonist, and Alice herself isn’t given much of a life or character outside of that sexual repression. Crucially, there’s little to no sense of what her home life or relationship with her parents are like, both of which are rather vital when the last 10 minutes shift into Lady Bird territory, so Dyer is left with the burden of carrying the film predominately on her shoulders.

Luckily for Maine, Dyer turns out to be up to that task. I’m one of about 40 people who has yet to watch any Stranger Things, so this is the first I’m seeing of her acting and she’s definitely been given the space to shine. Everything I said earlier about understanding Alice’s constant sense of shame and social discomfort is almost entirely down to Dyer’s persistently uncomfortable body language and just-exaggerated-enough facial expressions (clearly communicative but not tipping over into vaudevillian). She’s a fantastic, sympathetic and empathetic screen presence working overtime to bring together a consistent psychology to this character study that also ends up elevating much of the script’s weaker areas. For example, this at least part-comedy is severely lacking in laughs but Dyer’s convincing naivety and awkward impulsivity manages to raise at least a few titters from jokes and physical situations which are rarely as funny as the wildly inconsistent score by former Passion Pit member Ian Hultquist attempts to tag them as. Or maybe that’s just because I was naturally rooting for Alice (both due to Dyer and my own innate sympathy for teenagers being forced to deny their true selves by religious oppression) and so couldn’t join the film at its slight remove from the action on-screen, where it’s more focussed on the inherent humorousness of those in charge’s hypocritical anti-intellectual worldviews rather than grappling with the psychological effects of their actions.

And so it goes with Yes, God, Yes. Maine’s feature debut is a very solid watch, one designed to be agreeably light in the way many indie coming-of-age dramedies are, with a great central performance that hopefully indicates better things in store for them. But the film as a whole is forever at half-mast, frustratingly on the verge of its evident potential but never taking the additional steps required to fulfil it. Maine’s relative distance from the Catholic sect featured in the film means that, whilst she never actively demonises the religion itself (thankfully), we also never get to understand the alluring power of these retreats and their teachings or why anyone would fall for or be drawn to them. (Once again, Cameron Post didn’t shy away these kinds of complexities and came out a much better film for it.) Meanwhile, she also works really hard to replicate the aesthetic look and feel of a turn-of-the-millennium teen drama – right down to not at all being above utilising on-the-nose period-appropriate needle-drops to semi-trashy effect (this is easily the best usage of Collective Soul in anything ever) – but then cuts that hard work off at the knees by slathering this bizarre near-greyscale colour tint over the whole thing which makes every shot look like it’s been run through an Instagram filter, or that aforementioned part-synthwave part-xx score that’s all over the place.

I’m willing to cop to, despite my adoration for and constant seeing myself in teen girl coming-of-age dramedies, maybe just not getting Yes, God, Yes and it simply not being for me. But the fact remains that I was never able to get fully sucked in emotionally to events on screen. Maine displays very evident potential in terms of craft and ideas; I hope she gets further opportunities to develop and realise them. Dyer, at least, deserves an opportunity to lead something bigger and more complex post-haste. If you need a reason to give this brisk agreeable flick your time, it’s all on her.

Yes, God, Yes is available to rent and buy on Digital VOD platforms from tomorrow.