Words: Callie Petch

Those who’ve chosen to follow all of my increasingly sporadic and belated London Film Festival dispatches may have picked up on this year’s line-up being a Festival of B-Minuses, the Three-and-a-Half Star Festival for those who prefer number ratings. A whole lot of films that aren’t exactly bad but not really anything to excitedly write home about either. Some are disappointments relative to expectations or a filmmaker’s prior work, very little outright terrible – the sole film playing at the festival that scored lower than a C- on my gradebook was from nearly 30 years ago – but mostly these movies making up this year’s line-up were… fine. Just kinda fine.

As previously mentioned, there’s every chance my thoroughly whelmed reaction to much of the year’s line-up may have been due to seeing the wrong films, always a possibility at giant film festivals. Or it may have been due to the industry undergoing a completely understandable fallow year with a whole load of television shows, virtual reality shorts, and “extended reality experiences” having to artificially inflate the holes in the programme, like when a digital game storefront sale surrounds the few big-name titles with lots of cheap shovelware to make it seem like there’s more on offer than realistically appears. Whatever the case may be, I was a bit demoralised heading into the second Friday of the Festival, still waiting for the knockout blows to arrive. Not to dismiss or downplay The Power of the Dog and The First Wave, but I’d expect a two-week long film festival to have more than just two excellent movies to display, y’know?

Perhaps the festival was waiting until my 27th birthday to spring its best treats on me as a special present, cos that Friday (with the prior-covered exception of Benedetta) sprung all the hits on me at once. Technically, the party got started a day earlier when I saw CJ Hunt’s excellent documentary about Confederate statues in New Orleans and the normalised White supremacist history behind all such monuments, The Neutral Ground (Grade: A-). I’m not going to go into the film much here because it releases in the UK on 1st December and I have plans to do a proper full review plus a feature on the film for (hopefully) various places to coincide with the release. What I will say for now is that it is very special.

Perhaps the festival was waiting until my 27th birthday to spring its best treats on me as a special present, cos that Friday (with the prior-covered exception of Benedetta) sprung all the hits on me at once. Technically, the party got started a day earlier when I saw CJ Hunt’s excellent documentary about Confederate statues in New Orleans and the normalised White supremacist history behind all such monuments, The Neutral Ground (Grade: A-). I’m not going to go into the film much here because it releases in the UK on 1st December and I have plans to do a proper full review plus a feature on the film for (hopefully) various places to coincide with the release. What I will say for now is that it is very special.

Whilst it starts off as a Daily Show-esque ‘look at these fucking assholes’ satirical comedy, the documentary soon morphs into an entertainingly presented and highly interesting educational film which demonstrates how this micro problem – in which a lawful and democratically-decided process ends up being farcically drawn out to 551 days due to militant right-wing agitators and racialised threats of violence – reflects a macro issue of America (and by extension the Western world) still refusing to meaningfully grapple with their historical exploitation and subjugation of Black people thanks to decades of ingrained false-narratives. Only for that to eventually give way to a powerful exploration of one Black man’s effort to reconcile the reality that so many of these ignorant White people will refuse to change, and attempting to find self-care and healing in spite of that. It’s a stunning watch with a unique voice of its own, which even the already-converted can find themselves challenged and their understanding expanded by what Hunt’s camera captures. Again, more to say on the movie soon, here and (hopefully) elsewhere, but do not miss this.

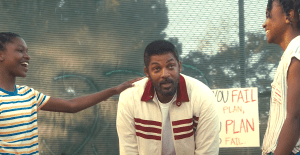

Then we hit Friday’s first film proper – there was also further Neutral Ground news I woke up to that morning, but again that’s for another day – and what turned out to easily be my biggest surprise of the festival. I did not expect to love King Richard (Grade: A-). Hell, I didn’t even expect to like King Richard. When it was announced that Warner Bros. were making a biopic about the Williams Sisters, Venus (Saniyya Sidney) and Serena (Demi Singleton), and their rise to tennis superstardom… from the perspective of their father, Richard (Will Smith), I freely admit to joining the mildly incredulous “da fuck you say?” crowd regarding the premise. Alarm bells which only rang louder upon release of the trailer which appeared to lean in hard and unquestioningly to the self-centred capitalistic American Dream myth that removed any potential agency from the young girls who would become two of the greatest tennis players of all-time. “I wrote me a 78-page plan for their whole career before they was even born” raises major red flags when parroted without surrounding context, let’s put it that way.

Then we hit Friday’s first film proper – there was also further Neutral Ground news I woke up to that morning, but again that’s for another day – and what turned out to easily be my biggest surprise of the festival. I did not expect to love King Richard (Grade: A-). Hell, I didn’t even expect to like King Richard. When it was announced that Warner Bros. were making a biopic about the Williams Sisters, Venus (Saniyya Sidney) and Serena (Demi Singleton), and their rise to tennis superstardom… from the perspective of their father, Richard (Will Smith), I freely admit to joining the mildly incredulous “da fuck you say?” crowd regarding the premise. Alarm bells which only rang louder upon release of the trailer which appeared to lean in hard and unquestioningly to the self-centred capitalistic American Dream myth that removed any potential agency from the young girls who would become two of the greatest tennis players of all-time. “I wrote me a 78-page plan for their whole career before they was even born” raises major red flags when parroted without surrounding context, let’s put it that way.

With context, however… goddammit if King Richard doesn’t work gangbusters! When not being extracted for ‘inspirational’ trailer montages, lines like that aforementioned “78-page plan” find themselves rooted in the harsh realities of life in impoverished early-90s Compton and the desire by a father constantly beaten-down because of his environment to not let the same happen to his children. Director Reinaldo Marcus Green lets the rosy sun-drenched heat of his early cinematography, where the joyful connection of the Williams family seems to light up everything surrounding them in a safe glow, dissipate just often enough, tapping into his breakthrough work on Monsters and Men, to communicate how that perpetual cycle of poverty-fuelled masculine violence is always just around the corner for all Compton residents; so tempting to slide into despite one’s better instincts. Contrasting with the cordoned-off privileged money of the upper-class White people who own the various tennis clubs Richard works one of his many jobs at; a gilded cage of faux-politeness and stability largely out of reach for an exceptional Black family from the ghetto.

As a result, Richard has to continuously myth-make and cheerlead for his family, pushing them to greatness and boasting about their virtues to anyone with ears and keys to the gates, since nobody else is going to. A society content to leave him, his loyal wife Brandy (Aunjanue Ellis), and their five daughters in the dust. It’s a surprisingly clever way to weave played-out biopic standbys – snobby rich characters dismissing the likelihood of the subject ever making it big, the inevitable media montage where the subject becomes a highly-buzzed about matter, drop-in cameos from big name stars of the time, a grand All or Nothing match at the climax – naturally into King Richard’s fabric. It’s actually very reminiscent of Dolemite is My Name, in that sense, where its disrespected and constantly overlooked protagonist with a gift of the gab and unwavering self-belief effectively writes his own biopic in real time. This, not coincidentally, is why the casting of Will Smith as Richard works. Few movie stars today have the ability that Smith did in his prime to project total confidence and control, something he taps back into with winning charm here whilst teasing out enough of Richard’s control-freak ego issues and wounded pride to add dimension to the role.

As a result, Richard has to continuously myth-make and cheerlead for his family, pushing them to greatness and boasting about their virtues to anyone with ears and keys to the gates, since nobody else is going to. A society content to leave him, his loyal wife Brandy (Aunjanue Ellis), and their five daughters in the dust. It’s a surprisingly clever way to weave played-out biopic standbys – snobby rich characters dismissing the likelihood of the subject ever making it big, the inevitable media montage where the subject becomes a highly-buzzed about matter, drop-in cameos from big name stars of the time, a grand All or Nothing match at the climax – naturally into King Richard’s fabric. It’s actually very reminiscent of Dolemite is My Name, in that sense, where its disrespected and constantly overlooked protagonist with a gift of the gab and unwavering self-belief effectively writes his own biopic in real time. This, not coincidentally, is why the casting of Will Smith as Richard works. Few movie stars today have the ability that Smith did in his prime to project total confidence and control, something he taps back into with winning charm here whilst teasing out enough of Richard’s control-freak ego issues and wounded pride to add dimension to the role.

Those manifest more in the story’s second half but also, cleverly, precipitate a minor shift in perspective and agency from Richard to the women in his life. Even before then, Brandy and the daughters all get wonderful underplayed moments of bonding and expression – one such, where Venus & Serena playfully mock the extremely fancy traditions of the rich tennis club they’re walking through, nearly brought the house down at my screening – which Green’s camera and Zach Baylin’s screenplay smartly choose to linger on. Times where Richard is not the complete and total centre of their orbit; in particular, the reveal of how Serena got her training when the family could only afford to get professional coaching for Venus lays important groundwork for that second half. That initial centralising of Richard’s viewpoint also functions as a way of firmly refuting his own tendency to think of himself as the driving protagonist of the story when, in reality, it’s the Williams’ standing together as a united family unit, crafting the foundation and shoring up the fall-back required for Richard’s hustle to work. When this thread comes to a head, Ellis gets to sew up her Best Supporting Actress nomination slot in a cathartic outburst of emotion the movie hints at bubbling up for a long time.

Credit: Warner Bros.

King Richard is quietly smart like that a lot more often that it’ll likely be given credit for. Another example: making Richard the initial audience POV means that at no point does the narrative or presentation ever put Venus against Serena or favour one over the other, as decades of sports media and the annals of statistical history are pathologically incapable of not doing. Venus gets to have her moment in the sun rather than being overshadowed by Serena’s later accomplishments, whilst the movie in- and out-of-universe shuts down the remotest possibility of sisterly resentment immediately through a perfectly balanced pep talk late in the last act. Sidney and Singleton aid all of this with a convincing sister dynamic and by being firecrackers of charisma who we’ll hopefully see even brighter things from in the future. At every stage where the film could risk coming off as cynical, calculated, or mere brand management, it instead cleverly twists things in a manner which is just impossible not to be charmed by. Green is too earnest, too sincere, and too good at the fundamentals of crowdpleasing filmmaking to let the worst-case scenario happen.

On that note, I just want to briefly highlight the tennis sequences. King Richard, thankfully, is not embarrassed by the fact that it is, structurally, an underdog sports movie. So, when it comes time for one or both sisters to step onto the court, these matches have a thrilling punch, immediacy, and tactility to them. Pamela Martin’s editing is clean and coherent, ditto Robert Elswit’s darting cinematography and, aside from a few deliberately stylised shots, if there are post-production corners being cut to artificially tidy up sloppy play, I couldn’t notice them. The final match is the culmination of all this and the screenplay’s democratic balancing of POV duties, resulting in a brilliant and satisfying duel.

I recognise this seems like a strange thing to single out for praise, particularly since it’s for the pettiest reason – my still not being over Battle of the Sexes’ awful tennis sequences, reflective of how ashamed it felt about fundamentally being a sports movie. But it’s one I make for it is indicative of the overall virtues King Richard has. A commitment to being an utterly winsome, charismatic, and deceptively smart crowdpleaser which, much like Richard’s hustle and grinding, cannot help but win over the steeliest of hearts after long enough exposure. You want to believe in the same way that Richard, Brandy, Venus and Serena do because they’re so sincere and confident about it. As I said, I didn’t expect to like King Richard going in. Coming out, it ended up being one of my favourite films of the whole year. Perhaps that’s the American Dream showing it’s still got a few potent doses to convert the cynics left in the tank.

I recognise this seems like a strange thing to single out for praise, particularly since it’s for the pettiest reason – my still not being over Battle of the Sexes’ awful tennis sequences, reflective of how ashamed it felt about fundamentally being a sports movie. But it’s one I make for it is indicative of the overall virtues King Richard has. A commitment to being an utterly winsome, charismatic, and deceptively smart crowdpleaser which, much like Richard’s hustle and grinding, cannot help but win over the steeliest of hearts after long enough exposure. You want to believe in the same way that Richard, Brandy, Venus and Serena do because they’re so sincere and confident about it. As I said, I didn’t expect to like King Richard going in. Coming out, it ended up being one of my favourite films of the whole year. Perhaps that’s the American Dream showing it’s still got a few potent doses to convert the cynics left in the tank.

Alright, let’s talk Céline Sciamma. Perhaps the pre-eminent French filmmaker working today, it’s been fascinating to watch her evolve over the past decade, particularly as a writer-director of queer feminist cinema. Bursting onto the scene in 2007 with the teenaged sexual-awakening Water Lillies, following it up in 2011 with the trans-undercurrent androgyny piece Tomboy, before cracking more mainstream attention with the César-nominated Girlhood in 2014. All of these films became renowned for the truthful writing of their young cast of characters and sensitive handling of issues relating to queer identity, the latter of which I don’t dispute but still feel the need to affix a heavy asterisk to. All three of those prior films never once come off as exploitative or misery porn – Sciamma’s directorial hand is too light, empathetic, and artistic for that to happen – but they were preoccupied with violence in its many forms in ways that can arguably be considered cis/straight-comforting. Girlhood had a lot of gang violence, Tomboy ends on a dispiriting note of violence against the soul of its lead protagonist who must conform to rigid gender binary, and Water Lillies’ big deflowering scene can be read in some corners as sexual coercion. Stuff that cis/straight audiences can witness, tut in an ‘oh, how sad’ manner, then go sip some Starbucks with their Tragic Queer narratives safely reinforced yet again.

On paper, Portrait of a Lady on Fire fit right into that tradition, its period tale of doomed lesbian love kept secret by a society which forbade such a thing. Except that, whilst not avoiding the inevitable heartbreak conclusion, Sciamma’s film was such a joyous and pleasurable work which refused to get hung up on that inevitability. After the courtship dance of the film’s first half has concluded, Portrait instead becomes a safe space of pure swooning queer romance unburdened by a need to keep secrets or risk conflict – similar treatment is also provided to an abortion and is similarly revelatory. Even when that enforced separation does come, it’s not depicted in a traumatic way a la the public humiliation of Tomboy’s protagonist and nor is it lingered on; that devastating last shot was explicitly about being glad it happened rather than sad it was over. Her prior films, both the ones she directed and the ones she merely wrote (including the exceptional stop-motion animation My Life as a Courgette), were always empathetic but Portrait arguably saw her move into cinema as a means of compassion.

Perhaps this, far more than it being a masterfully crafted and performed work, was why Portrait became such a sensation in arthouse and film nerd circles; an instantly acclaimed masterpiece whose stature has continued to grow in the two years since its release. Of course, a movie like Portrait sets up a whole weight of expectations and buzzing eyes on whatever its director chooses to follow up with. Every film Sciamma has made came with more burdensome expectations on quality and content than the last, but it certainly felt like the eyes of the entire London Film Festival were on her latest, given how long and immediate the queues for its two tiny in-person screenings ended up being. So, what has Sciamma done when expected to follow up such a sweeping, mythical, totemic work as Portrait of a Lady on Fire? In many respects, she’s stripped all the way down and made her most minimalist work yet.

Perhaps this, far more than it being a masterfully crafted and performed work, was why Portrait became such a sensation in arthouse and film nerd circles; an instantly acclaimed masterpiece whose stature has continued to grow in the two years since its release. Of course, a movie like Portrait sets up a whole weight of expectations and buzzing eyes on whatever its director chooses to follow up with. Every film Sciamma has made came with more burdensome expectations on quality and content than the last, but it certainly felt like the eyes of the entire London Film Festival were on her latest, given how long and immediate the queues for its two tiny in-person screenings ended up being. So, what has Sciamma done when expected to follow up such a sweeping, mythical, totemic work as Portrait of a Lady on Fire? In many respects, she’s stripped all the way down and made her most minimalist work yet.

Petite Maman (Grade: A), way more so than even Portrait which gained a lot of its power from artistic yet natural uses of the tool, is a film in which silence says more than words ever could. The opening scene establishes this almost immediately as young Nelly (Joséphine Sanz) wanders down a hall of the nursing home her Grandmother recently died in, past a line of quiet to near-silent rooms with residents she says a brief goodbye to. Nelly and her parents (Nina Meurisse and Stéphane Varupenne) pick up the remainder of Grandmother’s things, in particular her old walking cane, and then depart for the childhood home to clear it out ahead of selling. Each family member is hurting but unable to communicate that fact and the prospect of spending a weekend in her childhood home soon causes Mother to disappear, leaving Father the job of finishing up and Nelly nobody to talk to. It’s understandable why staying in this house might rattle a recently bereaved child. Cinematographer Claire Mathon (reuniting with Sciamma after Portrait) films these walls in the early going with an almost crushing mundanity, the potential wonder or magic the house and surrounding woodland may have once had just… gone. Compact, ordinary, empty even before the packing starts; if you’ve ever returned to a house from your childhood years later, you’ll know this feeling.

Nelly, being a child who is in that awful middle-spot of being old enough to know what death is yet not old enough to compartmentalise or fully process it, ends up closing off from her Father’s attempts to engage with her. But things take a turn for the wholesome upon, when walking through the woods, she meets Marion (Gabrielle Sanz), a girl her age who looks almost identical to her in the midst of building a treehouse, and whose own house looks identical to the one that Nelly is staying in. It’s at this point any traditional ideas about plot and conflict disappear entirely for what, cannily, resembles a warm hangout movie.

Nelly, being a child who is in that awful middle-spot of being old enough to know what death is yet not old enough to compartmentalise or fully process it, ends up closing off from her Father’s attempts to engage with her. But things take a turn for the wholesome upon, when walking through the woods, she meets Marion (Gabrielle Sanz), a girl her age who looks almost identical to her in the midst of building a treehouse, and whose own house looks identical to the one that Nelly is staying in. It’s at this point any traditional ideas about plot and conflict disappear entirely for what, cannily, resembles a warm hangout movie.

Nelly and Marion hit it off pretty much instantly, sharing similar treehouse design philosophies and a love of performance which manifests in adorably precocious plays where we discover Marion’s desire to become an actress. Outside of the plays, their words to each other are spare but considered and naturalistic in the way Sciamma can effortlessly pull off at this point in her career. Instead, much like the central dynamic of Portrait, the silences don’t need to be broken for long periods of time. The mundane act of simply being together, providing companionship in a remote emotional world, is enough and celebrated by Sciamma’s camera. A growing closeness and eventual honesty which is pure and ideal. The Sanz sisters are the latest non-professional Sciamma leads to put out beautifully genuine performances, especially since these characters are still young girls carrying heavy emotional baggage they are asked to plainly yet affectingly put out on display; Sciamma really does have the magic whisper when it comes to directing child actors.

Petite Maman is slight in runtime, a mere 72 minutes, and it never once aims for the grand presentational grandeur of Portrait. In tone and delivery, this is a modest picture. I can understand if one comes away wondering where the larger point was since, as mentioned, Sciamma’s camera is deliberately mundane and small the whole time, long stretches occur without any major dialogue, and there’s no massively obvious catharsis like all of her prior films provide in their final moments. But from its intimate scale, and without ever betraying that modesty, Petite Maman finds some extremely profound things to say about grief, the roots of sadness and how different generations can react to it, and a longing desire to have more time to connect with those we love. There is a twist of sorts – I use ‘of sorts’ since it’s less of a twist and more elucidating information attentive viewers will have already picked up on – which pushes Sciamma’s story into similar thematic realms as Studio Ghibli’s When Marnie Was There and Mamoru Hosada’s Mirai, but it’s underplayed like everything else in the film and all the better for it.

Petite Maman is slight in runtime, a mere 72 minutes, and it never once aims for the grand presentational grandeur of Portrait. In tone and delivery, this is a modest picture. I can understand if one comes away wondering where the larger point was since, as mentioned, Sciamma’s camera is deliberately mundane and small the whole time, long stretches occur without any major dialogue, and there’s no massively obvious catharsis like all of her prior films provide in their final moments. But from its intimate scale, and without ever betraying that modesty, Petite Maman finds some extremely profound things to say about grief, the roots of sadness and how different generations can react to it, and a longing desire to have more time to connect with those we love. There is a twist of sorts – I use ‘of sorts’ since it’s less of a twist and more elucidating information attentive viewers will have already picked up on – which pushes Sciamma’s story into similar thematic realms as Studio Ghibli’s When Marnie Was There and Mamoru Hosada’s Mirai, but it’s underplayed like everything else in the film and all the better for it.

Throughout, Sciamma keeps us visually, narratively and emotionally at the worldview of Nelly. That means a similar haunting washed-out view of Grandmother’s home, contrasting with a more vibrant and welcoming look to Marion’s. That means a preoccupation on the sweet connectivity the act of play and make-believe with another person, how that provides greater meaning and release than directly confronting wider philosophical questions they don’t have the vocabulary to understand yet. Accordingly, that also makes those times when Nelly or Marion do find the words to verbalise the incredible emotions they are saddled with all the more powerful. The exact moment I locked in on Petite Maman’s wavelength came when Nelly showed off her Grandmother’s walking cane and, with a mournful innocence which strikes that devastating balance of knowing what’s happened but not being capable of fully processing it, said “it still has her smell.” Because I understood that on a deep fundamental level. I still have a few minor trinkets of my grandfather’s (who passed away eight years ago today) and it’s for exactly that sentiment. Disarmingly simple and completely truthful.

If you feel a certain kind of way when watching, if you’re still hurting from a familial loss or have a complicated intimate relationship with your mother, Petite Maman will break you in its closing stages all without actively trying to. It may not have the same operatic flourish of a delivery as the closing shot of Portrait, but “you didn’t invent my sadness” utterly destroyed me to the same degree. Rather than focussing on the hurt these maelstroms of emotions cause, Sciamma has fully transitioned into crafting a cinema of healing and compassion. When the credits roll in silence, the heart sings songs.

Next time: Joanna Hogg wraps up her Souvenir duology, and Joel Coen presents The Tragedy of Macbeth.