Disclaimer: this review was made possible thanks to a screener provided by the film’s UK distributor, Curzon.

Despite the fact that they are often really bloody terrible, I find myself fascinated and drawn to movies examining our co-dependent relationships with technology and social media. Some of that, admittedly, is because I have a perverse curiosity with seeing writers and filmmakers who clearly have no real understanding or relationship with the mediums they’re attempting to skewer show their whole entire arse in inadvertently-hysterical, err, hysteria about them. Real “granddad doesn’t understand how the Sky remote works but moans about kids today and their square-eyes” energy that’s hilarious whenever it’s not insulting. The bit in Jason Reitman’s Men, Women & Children where Dean Norris presses a key to move an MMO avatar forward and jumps back in shock when said avatar moves as inputted has lived rent-free in my head since December of 2014. But there are genuine reasons beyond my Cronenbergian car crash fetish.

Despite the fact that they are often really bloody terrible, I find myself fascinated and drawn to movies examining our co-dependent relationships with technology and social media. Some of that, admittedly, is because I have a perverse curiosity with seeing writers and filmmakers who clearly have no real understanding or relationship with the mediums they’re attempting to skewer show their whole entire arse in inadvertently-hysterical, err, hysteria about them. Real “granddad doesn’t understand how the Sky remote works but moans about kids today and their square-eyes” energy that’s hilarious whenever it’s not insulting. The bit in Jason Reitman’s Men, Women & Children where Dean Norris presses a key to move an MMO avatar forward and jumps back in shock when said avatar moves as inputted has lived rent-free in my head since December of 2014. But there are genuine reasons beyond my Cronenbergian car crash fetish.

Social media, and the technologies that facilitate them, is so intrinsically a part of our day to day lives I’m innately curious to see how stories handle their effects. Both externally in narrative developments, although that usually just ends up as someone yelling a thing’s “gone viral!” to justify whatever needs to happen next, and internally in character sociologies. Because social media has changed the way that we interact with each other, seemingly irrevocably; that’s just a fact. It simultaneously brings us closer together, enabling instant communication with anybody anywhere at any time, whilst keeping us ever further apart, since no technological innovation can negate the inherent depersonalising distancing effect of online interaction. It simultaneously fosters a more empathetic and caring environment – a place for lonely people to find likeminded connections whilst learning and interacting with groups they may not normally have been able to, hopefully growing and developing as a person from that – and a more bitterly hostile and confrontational one, since these services are driven by engagement algorithms lacking any concept of nuance and dragging attempted conversations down as a result.

It’s complex, but it’s also fundamentally the logical extension of centuries-spanning tribal capitalist-indoctrinated human behaviour. Many of the negative effects from social media aren’t specifically endemic to the technology itself, I believe, rather that the technology exacerbates those effects from our pre-social media age. Narcissism, sociopathic dehumanisation of the other, the gradual poisoning and degradation of opinionated communication, a hunger for fame, parasocial relationships… none of these are new and so many lesser dramas about social media and new technologies fail to understand that. Instead settling on simplistic binary demonisation of the technology and people behind them which fundamentally misunderstands the root causes, presupposing that we’d all be sunshine and rainbows if the technology never existed. Dave Eggers’ The Circle, and its accompanying 2017 film adaptation by James Ponsoldt, is especially guilty of this but Charlie Brooker’s much-beloved Black Mirror has also slipped far more often into this trap than not the further into its run we get.

Photo ©Natalia Łączyńska, ©Lava Films

More importantly than misunderstanding the topics these lesser works attempt to explore, however, it also just makes for bad drama. The resultant stories lunge so heavily into misguided polemic that they forget to bring the characters, balance or empathy required to engage and make the experience less like a Bad Place TED talk. (See also: Transcendence, but really don’t.) A part of me feels like we’re going to have to wait until the generation which grew up with social media institutionalised start getting to tell these stories, but Matt Spicer’s outstanding Ingrid Goes West from 2017 remains one of the most acerbic, well-examined, and empathetic depictions of social media’s effects both good and ill in any form. So, maybe it’s more that you just need to be open-minded and willing to put the work in, like with anything in life.

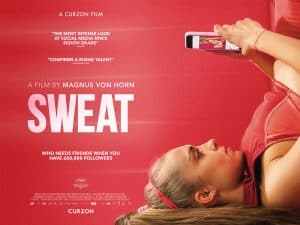

Magnus von Horn’s latest drama, Sweat, gets its subject better than any non-Ingrid attempt I have seen so far. Admittedly, this is because the film isn’t wholly about social media in the way that something like The Social Dilemma is. Instead, it’s a very 2020 portrait of modern loneliness – or, at least, a version of 2020 where the world didn’t end since this has been sat on the shelf for a year due to That Thing. Of a slowly crippling desire for some kind of true connection, particularly for those in the influencer lifestyle like our protagonist Sylwia (Magdalena Koleśnik). She’s a burgeoning fitness personality navigating three days in her life. Leading packed public group classes with adoring genuinely inspired fans, sharing motivational bon mots in her Insta stories and carefully-chosen #gymselfies, unboxing brand deals and taking Q&As on her live-streams, and preparing to go on Poland’s top morning show to spread her custom workout plans.

But Sylwia’s also crushingly lonely. Over the three days we spend with her – three deliberately and mostly uneventful days, that’s where the Polish cinema DNA really takes hold narratively – it becomes clear that she doesn’t really have much of a life outside of her vocation. No friends, no lovers, her mother (a brilliant and well-meaningly cold Aleksandra Konieczna) does not take much interest in her daughter’s success, and an existential self-doubt about whether anybody would really miss her if she just packed everything in and disappeared. But, of course, this is a real mental health strain she’s not allowed to show. As we join her, a clip of one of her late-night Live sessions has gone viral due to a tearful admission of loneliness and guilty jealousy towards her mother finding a new man, which gets her a casual dressing down from her manager because some of her brand endorsements worry “about their brand appearing in that context.” Nobody truly asks her if she’s ok, said manager clearly only does so out of concern for how it may affect both of their careers, and Sylwia herself doesn’t really seem to know how to fix it.

Photo ©Natalia Łączyńska, ©Lava Films

von Horn visually communicates that loneliness with an intimate yet cold and (thankfully) sexless camera. One that’s often physically close and fixated on facial close-ups, but never fully gives itself over to the potential emotion of the situation. There’s some kind of remove, some distancing observation effect which isolates Sylwia physically in a scene much like how she feels emotionally isolated every time she’s not switched-on for the ‘Gram. It works excellently, much more so than the usual physically distant austere camerawork found in many Polish dramas, and carefully considered by cinematographer Michal Dymek. It enhances the lack of connection and intimacy Sylwia feels, how tightly into her own head she gets when working out and the brief release it brings, and also how the world never really sees her as a person – instead a brand, or an idol, or an outlet to vent about their own traumas, or an attractive piece of meat to jerk to or try and fuck – without becoming overbearing or exploitative.

There’s an abiding empathy, here. Lesser examinations of social media stardom would preoccupy themselves with sniffy judgement of everything going on or be so concerned with trying to make a grandiose point that they would lose the central emotional core. But Sweat doesn’t do that. In fact, it offers not just empathy towards Sylwia but also dignity. It cares truly about her loneliness, her passive silent cries for help in a world largely uninterested in how she’s really doing, and is willing to meet her on those terms as much as the slightly-detached observational camera lets it. That’s something held together by Koleśnik’s great central performance as Sylwia. Soulful and silently spinning, yearning and disconnected, driven and doubtful; embodying these split halves of her personality, and the tangible switches from being “on” and “off” as it were, with realistic understandable coherency. You can tell when we’re seeing Sylwia and when we’re experiencing “Sywia,” if you get what I mean.

Although von Horn manages to get the empathetic, mostly non-judgemental examination of social media fame and its effects down pat, things get a little… iffier when he tries to apply that same eye towards the negative effects of parasocial relationships on social media. Specifically, Sylwia has a stalker, Rysiek (Tomasz Orpinski), introduced sitting in his car outside her apartment creepily watching and then, once confronted, masturbating in front of her as she attacks his car in an effort to drive him off. The encounter shakes her, naturally, even more so when he sends her an Instagram video the following morning in pathetic floods of tears apologising whilst also insisting that he thought they could be soulmates due to his belief that they are both similarly lonely souls needing comfort. When visiting her mother a day later and bringing up the experience at the dinner table, it becomes a divisive point of contention since Sylwia’s mother (and later several guests) try to discredit Sylwia’s emotions regarding the experience by subtly victim-blaming and trying to cast the stalker as a fundamentally decent man deep down who is just really lonely.

Photo ©Natalia Łączyńska, ©Lava Films

Without spoiling much more of what happens, theirs is an assessment which isn’t entirely wrong and, resultantly, shows a little more of von Horn’s male privilege in the process. To be clear, this is not saying that all stalkers are irredeemable creeps deserving of nothing but simplistic scorn, absolutely not. I get what von Horn is going for with this subplot. But the execution feels somewhat reductive and dismissive of the daily threat, both physically and mentally, that women in the public eye receive from social media stalkers in ways that also threaten to undermine the grace and dignity with which the film views Sylwia. In particular, the stretch where this strand comes to a head, intersecting with the tension between Sylwia and her stage-partner Klaudiusz (Julian Świeżewski), conceptually feels more at home in a significantly trashier film like Paul Verhoeven’s Elle than the measured piece von Horn is otherwise constructing. It threatens to take things off-rails.

Fortunately, the excellent ending sequence brings it all back, firmly rebuking the most cynical of reads one might have towards Sylwia whilst also refusing to offer an easy satisfying answer to those questions of her mental health or the intersection between being real on social media and “being real” on social media. Sweat is an affecting, nuanced, and understanding examination of loneliness in the digital age. One that gets the ways in which these services can exacerbate such social issues but also is fully aware of their true roots and makes all of this commentary through rather subtle and therefore moving filmmaking rather than didactic screeds. It’s not fantastic, and really does appear ready to fall apart during that aforementioned stalker stretch, but Koleśnik’s very strong lead turn never lets things slip into caricature and the film as a whole yearns for Sylwia to find that connection she needs so she no longer has to turn “on” and “off.” I hope so too.

Sweat releases in select cinemas and streams on the Curzon Home Cinema platform from Friday.

Words: Callie Petch