Troma Entertainment are legendary purveyors of independent schlock. Most famous throughout the 80s and 90s, Lloyd Kaufman’s notorious B-movie funhouse gained a reputation for making and distributing low-budget cult cinema which revelled gleefully in provocatively pushing all the buttons of good taste. Critics and even lovers of their work would label much of the production factory’s output as crass, exploitative, edgy, anarchistic or outright nihilistic in the sheer indulgence of sex, nudity, splatter or sadistic violence and habitual line-stepping they engaged in. They were habitual line-steppers.

But, beneath that adolescent provocation and the fluctuating quality inherent in a mass-producing low-budget cult cinema studio, Troma’s work really does care. Their best films have a heart and earnestness which stand in stark contrast to the most cynical of views usually placed on their work. Troma, for all their indulgence in bad taste, does have a screwed-on moral compass, one which rages against authoritarianism of all kinds, sticks up for weirdo losers, and is frequently fearlessly political with the exact kind of unsubtle execution one can expect from a studio which helped put out Surf Nazis Must Die. Big breakthrough The Toxic Avenger utilised its schlocky ‘scrawny nerd revenge power fantasy’ premise which other more (heh) toxic mainstream movies of the time played for meanspirited self-centred results – step right up, Fox’s horribly-aged Revenge of the Nerds series – to also flip middle-fingers at and inflict righteous vengeance upon governmental corruption and Reagan-era capitalistic exploitation. That’s not even getting into Troma’s War, a satirical action epic produced at the height of Reagan’s second presidential term as an explicit rebuke to both his and mainstream cinema of the time’s nationalistic glamourisation of war.

Credit: Jessica Miglio.

Copyright: © 2019 Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. All rights reserved.

James Gunn is a student of Troma. Literally, his career began as a protégé of Lloyd Kaufman and his first professional film credit was the screenplay for 1996’s Tromeo & Juliet, a Troma take on the Shakespeare staple. Although he was always adjacent to Hollywood before Marvel came calling, penning screenplays for both live-action Scooby Doo! movies and Zack Snyder’s Dawn of the Dead remake (all of which were allegedly hacked to death and rewritten by others during each’s production), Gunn spent much of the 2000s continuing to plough a Troma-esque trade. His web series P.G. Porn brought that provocative exploitation-satire to quickfire parodies of pornography. He worked with notorious Japanese game developer Suda51 on the batshit brilliance of teen-girl zombie hack-and-slasher Lollipop Chainsaw. His directorial debut, the criminally-underrated Slither, was both a loving homage to and pisstake of classic Cronenberg horrors.

Most important to understanding his career trajectory, in 2011, Gunn made Super. An ultra-pitch-black comedy in which Rainn Wilson and Eliot Page play deeply lonely and borderline-unhinged losers who become costumed vigilantes in an effort to exert some level of control over their miserable lives, Super can effectively be seen as Gunn’s mission statement as a storyteller. It’s relentlessly provocative, skipping back-and-forth over the border separating good and bad taste with little care for how offensive it may be. But, in between the occasionally disturbing violence, edgy attitude, and sometimes-indefensible lows all of its characters sink to, there is a genuine heart to it. Gunn zeroes in on the misanthropic tragedy of his two protagonists, their stunted self- and outwardly-destructive behaviours, and actively empathises with them even if he never fully absolves them; the results find a strange but legitimate catharsis regarding control of one’s own emotions. In many respects, it’s an even blacker and significantly more morally-ambiguous take on The Toxic Avenger.

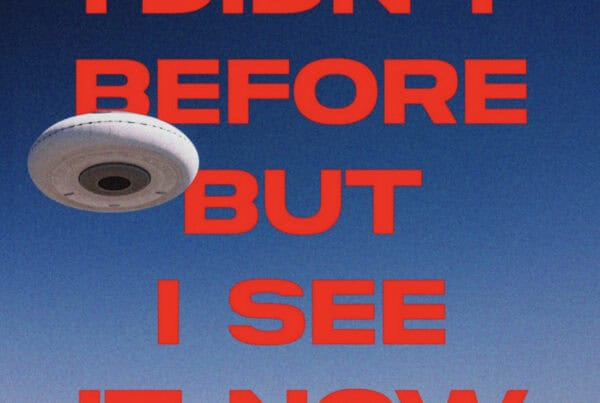

I begin with that lengthy dual-history lesson in hopes this next statement is better understood by those who don’t obsess over cult cinema 24/7: The Suicide Squad is a several-hundred-million-dollar Troma movie. It is not a do-over or continuation of the 2016 abomination yanked out of David Ayer’s hands at the last minute to undergo a half-finished hack-job by dumbass Warner Bros. execs and, in fact, this shall be the only time I’m going to reference that earlier thing in the entire write-up. No, The Suicide Squad is a mega-budget Troma film scurried into cinemas under the cloak of a tentpole mainstream superhero blockbuster. If that’s not apparent by the shot of Amanda Waller’s (Viola Davis providing her signature intimidating intensity) Task Force X – hardened/dumbass criminals and often unrepentant murderers forcibly conscripted as the face of America’s wet work – strolling in front of a giant American flag on their way to covertly invading a foreign country on a deniable ops mission, it will definitely be so by the time all hell violently breaks loose. A rug-pull of minor audaciousness for a mainstream crowdpleaser but perfectly in keeping with the anarchic B-movie subversions of a Troma flick, even before the title cards start coming into shape within the splattered brains of a dead soldier.

I begin with that lengthy dual-history lesson in hopes this next statement is better understood by those who don’t obsess over cult cinema 24/7: The Suicide Squad is a several-hundred-million-dollar Troma movie. It is not a do-over or continuation of the 2016 abomination yanked out of David Ayer’s hands at the last minute to undergo a half-finished hack-job by dumbass Warner Bros. execs and, in fact, this shall be the only time I’m going to reference that earlier thing in the entire write-up. No, The Suicide Squad is a mega-budget Troma film scurried into cinemas under the cloak of a tentpole mainstream superhero blockbuster. If that’s not apparent by the shot of Amanda Waller’s (Viola Davis providing her signature intimidating intensity) Task Force X – hardened/dumbass criminals and often unrepentant murderers forcibly conscripted as the face of America’s wet work – strolling in front of a giant American flag on their way to covertly invading a foreign country on a deniable ops mission, it will definitely be so by the time all hell violently breaks loose. A rug-pull of minor audaciousness for a mainstream crowdpleaser but perfectly in keeping with the anarchic B-movie subversions of a Troma flick, even before the title cards start coming into shape within the splattered brains of a dead soldier.

The Suicide Squad carries almost all of the hallmarks of a classic Troma piece, albeit thankfully sans the gratuitous nudity and threats of sexual assault against any characters. There’s a gleeful, sometimes glib approach to violence and death, sudden and extremely bloody, with almost every death of any named character (and there are A LOT of those) played for misanthropic comedy, like old Hollywood farces if their punchlines had access to Sam Raimi’s fake gore reserves. A thrilling almost-punk sensation to the filmmaking, flashy and fast-paced with hyper-colourful palettes and lighting, albeit freed from the budgetary constraints of real Troma. Meaning that Gunn can show a fish-human hybrid ripping a man in half in slow-motion, whose bloody viscera hangs in the air as a rainstorm fogs the surrounding area, whilst still having enough resources left over later for a kaiju to level half a city in similar detail. Sometimes, The Suicide Squad can get downright nasty with its refusal to shy away from just how low its villainous protagonists can sink, particularly Waller whose callous disregard for anyone and anything which gets in the way of the mission and frequent eliding of the full truth actively dehumanises all pulled into her orbit and for once is not painted as some kind of secretly altruistic “doing what needs to be done” necessity.

Gunn unapologetically provokes incessantly. Whether it be in the rare-for-a-blockbuster-nowadays level of violence, the submersion into a “bad vs. worse” central conflict and accompanying boisterous hedonism of that worldview, or just in the crassness of much of the dialogue – which flings fucks, dick jokes, and dick-swinging insults around with such frequency it’s like there was a special closing-down sale at his local juvenile comedy store – a lot of The Suicide Squad’s bolder moments could be seen as Gunn reasserting that enfant terrible reputation he used to sport as a badge of honour. “Oh, you thought I went soft after spending half-a-decade working for Marvel?” he seems to say, “Motherfucker, you could not be more wrong.” In particular, there’s a major tonal shift once the still-surviving members of The Squad make their way to the home of the mysterious Project Starfish which is somewhat reminiscent of his screenplay for 2017’s The Belko Experiment, and provides some genuinely unnerving body horror mostly accomplished by great practical effects which really ground things ahead of the expected CGI carnage finale.

Gunn unapologetically provokes incessantly. Whether it be in the rare-for-a-blockbuster-nowadays level of violence, the submersion into a “bad vs. worse” central conflict and accompanying boisterous hedonism of that worldview, or just in the crassness of much of the dialogue – which flings fucks, dick jokes, and dick-swinging insults around with such frequency it’s like there was a special closing-down sale at his local juvenile comedy store – a lot of The Suicide Squad’s bolder moments could be seen as Gunn reasserting that enfant terrible reputation he used to sport as a badge of honour. “Oh, you thought I went soft after spending half-a-decade working for Marvel?” he seems to say, “Motherfucker, you could not be more wrong.” In particular, there’s a major tonal shift once the still-surviving members of The Squad make their way to the home of the mysterious Project Starfish which is somewhat reminiscent of his screenplay for 2017’s The Belko Experiment, and provides some genuinely unnerving body horror mostly accomplished by great practical effects which really ground things ahead of the expected CGI carnage finale.

But, and this is crucial, all of that provocation and relentless style ends up being for a point because, like all the best Troma works, beneath the edgy irreverence and flirtations with nihilism is a film with a heart and screwed-on worldview. For one, befitting the most beloved Troma films, The Suicide Squad is staunchly and unsubtly against American interventionism and exceptionalism as well as authoritarianism of all kinds, working that into the narrative and filmmaking at every opportunity. There’s the aforementioned opening flag line-up. One of the meanest such examples comes relatively early on when the comedic slaughter of a makeshift village of guards, which occurs equally just as much from Bloodsport (Idris Elba getting to utilise his winsome lead charisma in a good film) and Peacemaker (John Cena merrily subverting his all-American patriot image to deluded and sinister ends) having a dick-measuring contest as it does Waller’s intel, builds to a punchline that flips the entire sequence on its head in a manner which makes it very clear who’s to blame without being a joy-killing audience scolding gotcha.

A brutal late-film fistfight for the very soul of America, its idealistic self-image vs. its self-interested reality, is largely shot in the reflection of a helmet worn by one of its participants. A not-insignificant amount of time is spent checking in with mission control, a Cabin in the Woods-esque bunch of largely-desensitised pencil pushers who place bets on which squad member will be the first to bite it. Harley Quinn (Margot Robbie who has completely owned the role in live-action by this point) spends a prolonged stretch in sort-of captivity to the island’s illegitimate president who wishes to romance and domesticate her in a warping of the rebellious image she propagates and that his coup co-opted for their own means. Alarm bells may ring at that premise – I know that my notorious Birds of Prey-stanning arse did have Harley down as the one potential red flag going in – but Gunn’s screenplay and Henry Branham’s cinematography afford her agency and dignity at every turn, even if said agency can be a little unconventional and misinterpreted. It even builds off of the work Cathy Yan did with the character in that prior movie rather than restating or redoing the earlier character development and, in its gloriously excessive collision back into the main plot, gifts Harley the film’s most vivid and fun action beat as a giant middle-finger to patriarchal despots the world over.

A brutal late-film fistfight for the very soul of America, its idealistic self-image vs. its self-interested reality, is largely shot in the reflection of a helmet worn by one of its participants. A not-insignificant amount of time is spent checking in with mission control, a Cabin in the Woods-esque bunch of largely-desensitised pencil pushers who place bets on which squad member will be the first to bite it. Harley Quinn (Margot Robbie who has completely owned the role in live-action by this point) spends a prolonged stretch in sort-of captivity to the island’s illegitimate president who wishes to romance and domesticate her in a warping of the rebellious image she propagates and that his coup co-opted for their own means. Alarm bells may ring at that premise – I know that my notorious Birds of Prey-stanning arse did have Harley down as the one potential red flag going in – but Gunn’s screenplay and Henry Branham’s cinematography afford her agency and dignity at every turn, even if said agency can be a little unconventional and misinterpreted. It even builds off of the work Cathy Yan did with the character in that prior movie rather than restating or redoing the earlier character development and, in its gloriously excessive collision back into the main plot, gifts Harley the film’s most vivid and fun action beat as a giant middle-finger to patriarchal despots the world over.

Every wild choice, every go-for-broke stylistic quirk, even most of the expected somewhat-on-the-nose needle-drops – although just as much audio real estate has been handed over to John Murphy’s crunchy yet surprisingly-capable-of-tenderness post-rock score; think a slightly more accessible version of his 28 Days Later work – it’s all in service of those themes. Actively tapping into the social commentary inherent in the premise and not only doing so in a deceptively smart way but one that doesn’t sacrifice crowdpleasing popcorn blockbuster fun-times in the process. A film where sometimes ugly confrontations of America’s broken and dehumanising prison industrial complex share screen space with a shark-man who nonchalantly refers to potential human snacks as “nom-nom”s. A film co-starring a death-seeking man who shoots glowing boils that look like polka dots (David Dastmalchian) and sees the face of the mother who experimented on and abused him everywhere, simultaneously one of the movie’s funniest recurring gags with a killer payoff and also one of its most poignant characters thanks to Dastmalchian’s star-making turn and the grace with which Gunn’s screenplay affords him.

See, again, Troma cared deep down. In a somewhat misanthropic way bordering on outright glibness, sure, but its various best disciples did care for their protagonists. Gunn’s screenplay and direction frequently let the air out of proceedings for a great dark gag, perhaps never better than the anticlimactic beginning to the opening beach assault, but he also knows exactly when to stop joking around and treat things with the seriousness that they deserve. When to fully acknowledge the ugly truth of certain cast members and when to afford them moments of legitimate sweetness (even if those may be spiked with vicious blood-thirsty teeth later on).

See, again, Troma cared deep down. In a somewhat misanthropic way bordering on outright glibness, sure, but its various best disciples did care for their protagonists. Gunn’s screenplay and direction frequently let the air out of proceedings for a great dark gag, perhaps never better than the anticlimactic beginning to the opening beach assault, but he also knows exactly when to stop joking around and treat things with the seriousness that they deserve. When to fully acknowledge the ugly truth of certain cast members and when to afford them moments of legitimate sweetness (even if those may be spiked with vicious blood-thirsty teeth later on).

This is where Gunn’s time shepherding the Guardians of the Galaxy duology really pays off. On a tonal front, he plants that seed of sweetness sneakily early and keeps it specific to certain characters whose heart radiates outward, making the eventual finale, the point where we find out whose lines are considerably more firmly-drawn than others’, earn its big emotional swings rather than coming off as insincere. On a character front, almost every single member of his massive cast is noticeably distinct from each other and, remarkably, from his Guardians work. One might have expected King Shark to be a blatant Groot expy, right down to being given an adorably lunkheaded monosyllabic voice by an action star (Sylvester Stallone in this case), but King Shark is more like a child than even Baby Groot was and has a subtle insecurity streak which just makes him weirdly lovable in between all the head munchings. And on a mechanical front, everybody gets a moment to shine. The losers brought in to add to the body count, the many red herring targets, even the giant CGI-heavy finale – one where, at long last, Gunn is able to noticeably stamp his entire mark on proceedings with complete control instead of getting lost in the noise of the pre-vis second-unit department – they all get something big, notable and memorable to do in their brief screentime. This in a movie with upwards of 25 named characters; Gunn makes it look effortless.

Hell, Gunn makes the entire thing look effortless. I’m honestly struggling to come up with meaningful critiques to levy against The Suicide Squad. Maybe its scope could have been wound in just a tad in order to make a slightly tighter edit? The propensity for non-chronological hopping back-and-forth to different groupings when separated can create these very occasional moments where the various individual narrative threads seem slightly disjointed or the momentum gets a bit stunted by the need to rewind four-and-a-half minutes to fill in what was going on a dozen floors further up. But those are extremely rare blips and the kind which are more than forgivable with the ambition displayed elsewhere and the otherwise virtuosic control Gunn has on every other facet. Almost every joke lands, every character makes an impression, every action scene thrills, every big flashy shot carries such bountiful meaning and striking effect. My god, I haven’t even talked about the decision to project Ratcatcher II’s (Daniela Melchior) flashbacks on the window of the bus the Squad is riding on; the grimy nature of the bus perfectly fitting her adolescence raised homeless on rat-infested streets by her father, with the sepia tone of said flashbacks communicating the lack of shame she feels about such a situation!

Hell, Gunn makes the entire thing look effortless. I’m honestly struggling to come up with meaningful critiques to levy against The Suicide Squad. Maybe its scope could have been wound in just a tad in order to make a slightly tighter edit? The propensity for non-chronological hopping back-and-forth to different groupings when separated can create these very occasional moments where the various individual narrative threads seem slightly disjointed or the momentum gets a bit stunted by the need to rewind four-and-a-half minutes to fill in what was going on a dozen floors further up. But those are extremely rare blips and the kind which are more than forgivable with the ambition displayed elsewhere and the otherwise virtuosic control Gunn has on every other facet. Almost every joke lands, every character makes an impression, every action scene thrills, every big flashy shot carries such bountiful meaning and striking effect. My god, I haven’t even talked about the decision to project Ratcatcher II’s (Daniela Melchior) flashbacks on the window of the bus the Squad is riding on; the grimy nature of the bus perfectly fitting her adolescence raised homeless on rat-infested streets by her father, with the sepia tone of said flashbacks communicating the lack of shame she feels about such a situation!

It just rules. The Suicide Squad just rules. I honestly think it may be the best DC film ever made. Not just the DC Extended Universe that Warner Bros. continue to cling onto like a life raft whose giant gaping hole has been covered by industrial strength duct tape mid-sink, but in all four decades of them making DC movies. I was ready to run through walls as I walked out of this thing, I was that joyously amped up by the magnificent cinema I had just watched. If nothing else, The Suicide Squad is definitely James Gunn’s masterpiece. The movie that the Troma protégé has spent his entire career preparing to make. One which synthesises his agent provocateur cult exploitation origins with the refined, openly-heartfelt finesse and near-unlimited canvas of his time in mainstream blockbuster filmmaking, bringing both sides together in order to demonstrate, through an astonishing understanding of how to craft a popcorn crowdpleaser, how the two aren’t so far different as they may initially seem. Something which could only come from his horribly beautiful mind.

The Suicide Squad is playing in theatres nationwide now.

Words: Callie Petch