Disclaimer: this review was made possible thanks to a screener provided by the film’s UK distributor, National Geographic Documentary Films.

Disclaimer: this review was made possible thanks to a screener provided by the film’s UK distributor, National Geographic Documentary Films.

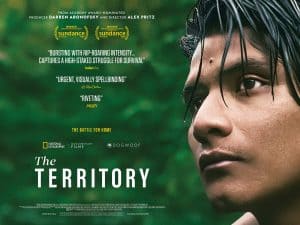

Alex Pritz’s feature debut, The Territory, functions far more as a vital piece of advocacy work than your usual documentary but, given the subject matter, that’s certainly no bad thing. Chronicling four years in the rainforests of Brazil’s Amazon, we are placed ground-level with the indigenous Uru-eu-wau-wau tribe as they battle against an increasing encroachment of illegal land-grabs in their rightful protected homelands. As the opening crawl informs us, the tribe were only contacted by the Brazilian government in the 1980s when they numbered in the thousands, but their population count has been reduced to less than 200 by the time Pritz’s cameras begin rolling. “Settlers” and miners and farmers all trying their best to forcibly take the land and its resources from the tribe despite both its colonialist illegality and the devastating wider damage such actions facilitate.

Pritz provides four key points of view, crossing both sides of the divide in the process. There’s the Uru-eu-wau-wau tribe themselves with focus coming primarily from Bitaté, a young man who is quickly ascended to tribe leader as the invasions continue to grow. Aiding him and second-in-command Ari is Neidinha, a fierce environmental activist who has spent and will continue spending every waking second of her life fighting on behalf of the tribe and the lands that are rightfully theirs in spite of the Indigenous Affairs Agency’s ineffectual help and a torrent of death threats against her. Then, on the other side, there’s Sérgio, a disgruntled 49-year-old farmer who feels a lot of disillusioned ‘economic anxiety’ over his lot in life and, emboldened by the newly-elected far-right President Jair Bolsonaro, forms an Association with other likeminded people to lobby the government to legally turn over the tribal land to themselves. Lastly, Pritz manages to also embed himself with Martins, a (what the subtitles almost mockingly term) “settler” who makes frequent journeys into the protected land to build himself a house he believes is rightfully his by cutting and burning the rainforest down.

An invader rides his motorcycle through the rainforest fire blaze. (Credit: Alex Pritz/Amazon Land Documentary)

Despite what one may assume when providing so much screen and verbal-time to White people actively destroying and colonising land which is not theirs – even if the infrequent uninterrupted filming of Martins burning entire sections of rainforest over the course of several years does raise a few questions about documentarian ethics – Pritz isn’t remotely sympathetic to their cause. In fact, he and Carlos Rojas Felice utilise tight editing to demonstrate just how quickly the smokescreens of capitalistic disillusionment and religious fervour dissipate to reveal plain old racism and colonialist entitlement as the primary fuel source of these invasions. An astonishing, almost proud ignorance of both history and their own effects on the land around them juiced up by President Bolsonaro’s rhetoric and tacit approval.

It’s uncomfortable viewing but in an intentional provocative manner designed to spur strong emotional responses since, as Bitaté notes, the protected rainforest his tribe lives in is a vital part of the entire earth’s ecosystem. Its destruction would be catastrophic for more than just the population of the Uru-eu-wau-wau tribe, although that’s not to downplay the tribe’s own precarious living situation. There’s a quietly moving exchange early on where one of the village elders speaks wistfully about just how quickly the tribe’s population and culture have degraded since first contact with the Brazilian government three decades ago. He doesn’t offer much in the way of specifics, but that very fact itself conveys the extent of the damage inflicted upon these people by invaders like Martins and Sérgio over the years.

Sergio, leader of the Association of Rio Bonito. (Credit: Alex Pritz/Amazon Land Documentary)

Pritz arranges his – and, later, Tangãi Uru-eu-wau-wau’s once the tribe begin to take matters into their own hands with their own media advocacy crew – footage with the propulsion, tension and urgency of a thriller. There are alternately gorgeous and haunting images of the rainforest in both its natural beauty and its devastating destruction. One early drone shot manages to capture both extremes at the same time as it rises over the luscious plant-life of the tribe lands to survey the burned-out greying deforestation not too far away from where the group are currently stationed, cut along fine regimented lines. Katya Mihailora’s score often rides an escalating beat to emphasise the ticking clock nature of the situation, incorporating vocal noises which are almost tribal. It’s all undoubtedly effective, even before taking into account the death threats and fatal acts of violence inflicted upon those just trying to live and those just trying to advocate for their right to live.

Yet, I’d argue that The Territory is never better than when the story gets to 2020 and, thanks to COVID safety measures the Uru-eu-wau-wau tribe pointedly adhere to (unlike certain Brazilian presidents), Pritz has to cede the floor to the tribe. Armed with their own cameras, their own drones, and a plan to bring wider exposure to their situation in the face of governmental indifference via dangerous self-patrols. Crucially, you also get more glimpses into their tribal culture and individual characters that Pritz’s footage seems to largely leave out, in line with Bitaté’s desire to preserve and archive their language and culture in case the worst occurs. I would have liked much more of that especially in the film’s earlier going, where the tribe got to display a little more character and agency so that Pritz wouldn’t inadvertently define his central subjects, the people he’s advocating for, predominately by the suffering and injustice happening to them.

I get why this is the case – especially when the reality of the situation did mean that the tribe were stuck in a rock and a hard place for so long, devoid of agency – and is more of a personal hang-up than anything else. Pritz wants to spur change, to paint a picture in no uncertain terms of how dire things were and continue to be for the Uru-eu-wau-wau people. The Territory is most certainly effective in that regard. An often harrowing and admirable piece of journalistic activism which refuses to let this issue go down without a fight.

![]()

The Territory is playing in select cinemas from tomorrow.

Words: Callie Petch