Disclaimer: this review was made possible thanks to a screener provided by the film’s UK distributor, Munro Film Services Ltd.

The vast majority of music documentaries follow a pretty strict formula. Open on a montage of good times usually accompanied by vague voiceover rhapsodising bona fides of the subject in question whilst simultaneously alluding to internal strife to come down the line, accompanied by the artist’s biggest hit on the soundtrack. Rewind back to the early days, plenty of home video footage and talk about it being “fate” that these important people all found each other when they did. Pre-fame gig footage, perhaps with a foreshadowing “things were simpler/more fun back then” variant, plus more props being given by peers about the subject’s evident talent. The good times fame montage brought to a screeching halt by somebody mentioning that “the band was falling apart” or something like. Hash out the dirt shit, the All is Lost moment, triumphant reunion/water under the bridge, not so subtle messaging that the band/artist is likely touring near you today… You know the drill.

The vast majority of music documentaries follow a pretty strict formula. Open on a montage of good times usually accompanied by vague voiceover rhapsodising bona fides of the subject in question whilst simultaneously alluding to internal strife to come down the line, accompanied by the artist’s biggest hit on the soundtrack. Rewind back to the early days, plenty of home video footage and talk about it being “fate” that these important people all found each other when they did. Pre-fame gig footage, perhaps with a foreshadowing “things were simpler/more fun back then” variant, plus more props being given by peers about the subject’s evident talent. The good times fame montage brought to a screeching halt by somebody mentioning that “the band was falling apart” or something like. Hash out the dirt shit, the All is Lost moment, triumphant reunion/water under the bridge, not so subtle messaging that the band/artist is likely touring near you today… You know the drill.

That’s not to ding such documentaries for adhering to well-worn tropes. Rather, to point out that the vast majority of them are regimented constructions designed to play to their respective fanbases rather than win over any new converts. Fundamentally, they function as Wiki glossaries with the added benefit of sound and video communicating the words. The best ones may break from that formula through disarming levels of access and utilising their subject as a vessel to explore topics beyond pumping up the myth of an artist/band – just this year, for example, The World’s a Little Blurry did exactly that for pop megastar Billie Eilish, parlaying intimate access into a very effective communication of whirlwind fame on youth and mental health. But you can also make a great music doc whilst sticking to the aforementioned conventions simply by artfully arranging those pieces in compelling ways, building up a solid argument as to why the artist is deserving of the legacy a feature documentary helps burnish, or just having a lot of really entertaining archive footage and anecdotes – step right up, Supersonic.

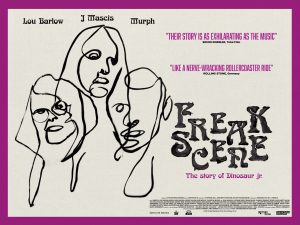

Freakscene, Philipp Reichenheim’s ode to the music and impact of cult alternative rock trio Dinosaur Jr., does neither of those things. Fundamentally, it’s a formulaic music documentary playing to the band’s fanbase and lacking any real insight into either the music or their legacy despite a murderer’s row of big rock names on the interviewee side – Thurston Moore and Kim Gordon of long-time friends Sonic Youth, Kevin Shields of My Bloody Valentine, Henry freakin’ Rollins, to name a few. There’s plenty of home video and early gig footage, most of the latter having its master audio replaced with that of the studio recordings presumably because of their low quality. The structure is the same as so many other music docs throughout the years, and in general isn’t very illuminating for anyone who doesn’t know their I Bet on Sky from their Sebadoh. So far, so run of the mill.

Freakscene, Philipp Reichenheim’s ode to the music and impact of cult alternative rock trio Dinosaur Jr., does neither of those things. Fundamentally, it’s a formulaic music documentary playing to the band’s fanbase and lacking any real insight into either the music or their legacy despite a murderer’s row of big rock names on the interviewee side – Thurston Moore and Kim Gordon of long-time friends Sonic Youth, Kevin Shields of My Bloody Valentine, Henry freakin’ Rollins, to name a few. There’s plenty of home video and early gig footage, most of the latter having its master audio replaced with that of the studio recordings presumably because of their low quality. The structure is the same as so many other music docs throughout the years, and in general isn’t very illuminating for anyone who doesn’t know their I Bet on Sky from their Sebadoh. So far, so run of the mill.

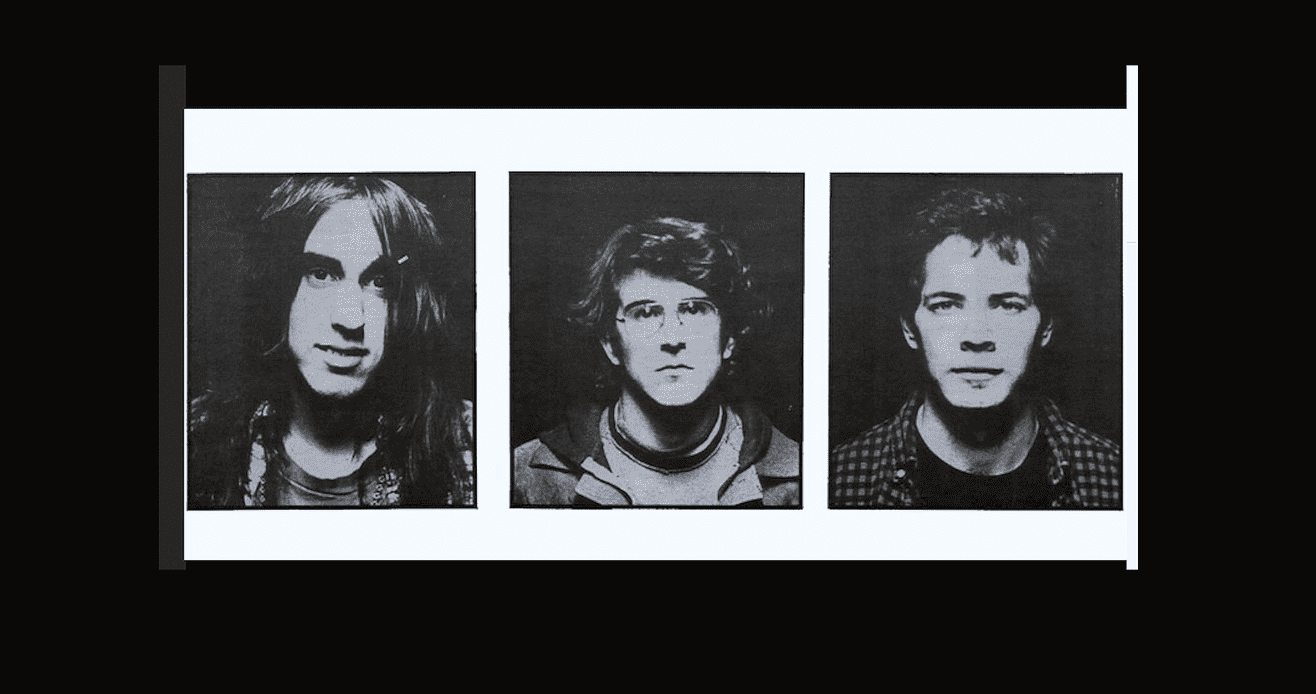

What’s interesting about the film, however, is how this all feels rather intentional, and I don’t mean that in the “these filmmakers are trying to slop out any half-effort tripe for cheap money” way. Freakscene’s myriad of faults to me feel like intended design decisions meant to both place the focus primarily on the music rather than the three guys – J. Mascis (lead singer and guitarist), Lou Barlow (bassist and singer), and Murph (drummer) – responsible for making it and also communicate the essence of their fragmented, slightly-abrasive, no gimmicks music in-film. Where Dinosaur Jr. songs just seem to appear out of thin air, looking effortless and shorn of any real indulgence (on-record), getting straight to their unconventional pop centres without getting bogged down by unnecessary drama or fluff. Straight-talking, for all the scruffy fuzz and power, yet also like being welcomed into some cool secretive group that those on the outside won’t get.

At least, that’s the reason I’m settling on for a movie this choppily edited, to such a degree that it has to intentional and especially since it barely gets to 75 minutes when the end credits are taken out. The narrative runs in chronological order – beginning with J. Mascis and Lou Barlow’s teenaged start in Westfield hardcore band Deep Wound, the formation of Dinosaur and J switching to guitar, their friendship with Sonic Youth, J’s tyrannical dictatorship of the music, the Jr. addition, tensions boiling over during the recording of seminal album Bug, and so on and so forth. But each segment lacks real context or clear signposting. Many interviews with the band members especially almost cut in halfway through without proper set-up. Lou’s frustrations with J’s control first show up almost mid-digression, one minute he’s ecstatic about how the band’s sound is coming together and the very next he’s heated at not getting a creative say. J’s anecdotes and stories frequently trail off into nothingness. Decades pass by without any prior warning more than once.

At least, that’s the reason I’m settling on for a movie this choppily edited, to such a degree that it has to intentional and especially since it barely gets to 75 minutes when the end credits are taken out. The narrative runs in chronological order – beginning with J. Mascis and Lou Barlow’s teenaged start in Westfield hardcore band Deep Wound, the formation of Dinosaur and J switching to guitar, their friendship with Sonic Youth, J’s tyrannical dictatorship of the music, the Jr. addition, tensions boiling over during the recording of seminal album Bug, and so on and so forth. But each segment lacks real context or clear signposting. Many interviews with the band members especially almost cut in halfway through without proper set-up. Lou’s frustrations with J’s control first show up almost mid-digression, one minute he’s ecstatic about how the band’s sound is coming together and the very next he’s heated at not getting a creative say. J’s anecdotes and stories frequently trail off into nothingness. Decades pass by without any prior warning more than once.

It’s certainly reflective of J’s public and artistic persona, if nothing else – vague, guarded, soft-spoken, yet still having an unmistakable aura of some kind – and none of the guys seem like easy interviewees. J especially seems to have the resolve of Jack Bauer being tortured by terrorists, trying to get this man to open up meaningfully about anything is like drawing blood from a stone, and Lou’s terse summation for why he clashed so heavily with J early on being “I wasn’t mature, I grew up, that’s it” perhaps indicates wounds he’d rather not reopen. But it means that the film’s flow feels disjointed and half-formed as a result, and the narrative (such as it were) ends up lacking much in the way of detail. The band, the music, the influence, the reunion and continued creative partnership… It can all be traced back to two very early nuggets – that the search for ear-splitting noise and fuzz was a by-product of their being early progenitors of post-hardcore, and a shared creed that they never set out to “have fun” playing music – which never get built upon from there. Maybe that’s true, and both foundations were admirably held to for their entire career, but it doesn’t make for an interesting story.

By and large, the music gets left to do the real talking. Almost literally, at that, since the opening and closing five minutes are dedicated exclusively to montages set to the titular “Freak Scene” which does little to dissuade assumptions that Reichenheim was badly stretching for that feature-length designation in the edit bay. Whenever the trio prove less than reticent to chat about their art – I don’t even think there’s a single moment in the film where the writing or recording process gets properly talked about, come to think of it – a new track will be cued up for a bit to play over file footage and talking head bits intentionally shot with a jerky extreme-close-up home video aesthetic. Again, in a way, that is admirable. Why have dozens of quick-cameoing rock critics and historians or famous fans pop in to say “the music was incredible” when you can just, y’know, play the songs and let the audience decide for themselves that “hey, this music is pretty darn good.” But that’s also something one can do by just… playing some Dinosaur Jr., maybe booting up a *chokes back vomit* Spotify playlist of their big hits and heading to Genius.com. One doesn’t need the film in order to do that.

By and large, the music gets left to do the real talking. Almost literally, at that, since the opening and closing five minutes are dedicated exclusively to montages set to the titular “Freak Scene” which does little to dissuade assumptions that Reichenheim was badly stretching for that feature-length designation in the edit bay. Whenever the trio prove less than reticent to chat about their art – I don’t even think there’s a single moment in the film where the writing or recording process gets properly talked about, come to think of it – a new track will be cued up for a bit to play over file footage and talking head bits intentionally shot with a jerky extreme-close-up home video aesthetic. Again, in a way, that is admirable. Why have dozens of quick-cameoing rock critics and historians or famous fans pop in to say “the music was incredible” when you can just, y’know, play the songs and let the audience decide for themselves that “hey, this music is pretty darn good.” But that’s also something one can do by just… playing some Dinosaur Jr., maybe booting up a *chokes back vomit* Spotify playlist of their big hits and heading to Genius.com. One doesn’t need the film in order to do that.

So, Freakscene joins the long list of music docs which aren’t particularly illuminating and can’t really be recommended to anybody not already a fan of the band in question. I’m also not entirely confident that fans would get much out of it either, since there aren’t any juicy stories or new and/or profound insights hitherto unknown, unless they really got a jonesing for 80s-era concert videotapes. Yet I can’t help but find it somewhat interesting, even if it’s extremely difficult to recommend. Its failures do seem to come from an intended artistic vision, an effort to translate the vibe and style of its subject into a different medium, albeit perhaps a misguided one with content as thin as what I’m presuming Reichenheim had to work with. They tried a different swing, it didn’t work out, but hey they tried that “different” at least.

Freakscene: The Story of Dinosaur Jr. is now playing in select cinemas.

Words: Callie Petch